How can companies adapt to the circular economy?

At a seminar on circular material flows and detoxification, Professor Mattias Lindahl outlined some core principles for organisations to follow in the circular transition. As he explains, this shift means rethinking old strategies and business models and reframing outdated ideas around waste.

07 Jan 2025As an expert in ecodesign and business models, Lindahl played a key role in crafting a new standard that defines core concepts and guidance for the circular economy, released in 2024. The Linköping University professor presented these ideas in his talk “Circularity and detoxification for future resources”, delivered at Framtidsdagen (Future Day) 2024. That seminar, hosted by Ragn-Sells and the Ragnar Sellberg Foundation, focuses on new trends and technologies in circularity and recycling, with the 19th instalment centred on the theme of detoxification.

The new standard – ISO 59000 – includes six principles for organisations to follow in the circular transition: systems thinking, value creation, value sharing, resource stewardship, resource traceability, and ecosystem resilience.

In his presentation, Lindahl traced the history of how some of these concepts have developed from before the 19th century to now. The norm of, for instance, repairing and reusing goods was replaced by an era of overconsumption as manufacturing grew more complex. But a circular economy means returning to some of those old ways.

– They make sense in a more circular economy when you're not just selling the product but actually are focusing on the provided value over time, he said.

Professor Mattias Lindahl at the seminar Framtidsdagen (Future Day).

Professor Mattias Lindahl at the seminar Framtidsdagen (Future Day).

Optimising with a sustainability mindset

According to Lindahl, one pattern to leave behind in a circular transition is the single-minded drive towards more efficient processes. While efficiency is of course important, it should never be the primary aim.

– The starting point should always be what is the most effective thing to do, what is the right thing to do, and then we should make that efficient, he said.

In the past, manufacturers have optimised their systems without much thought towards the environmental impact. Lindahl highlighted the plastics sector as an example, where increased efficiency in production has led to thousands of materials being mixed together, creating hazardous substances. This makes sorting plastic waste difficult and even dangerous.

He initiated a project called Unity that surveyed the sector about a potential solution. If thermoplastics were standardised to reduce additives, there would be fewer types of material but still a suitable range for broader use. This would bring detoxification right into the design phase, resulting in fewer contaminants and safer sorting after the use phase.

Even the plastics producers who were surveyed found the idea promising – an efficiency based on prioritising safe and effective material flows.

New models to meet customer needs

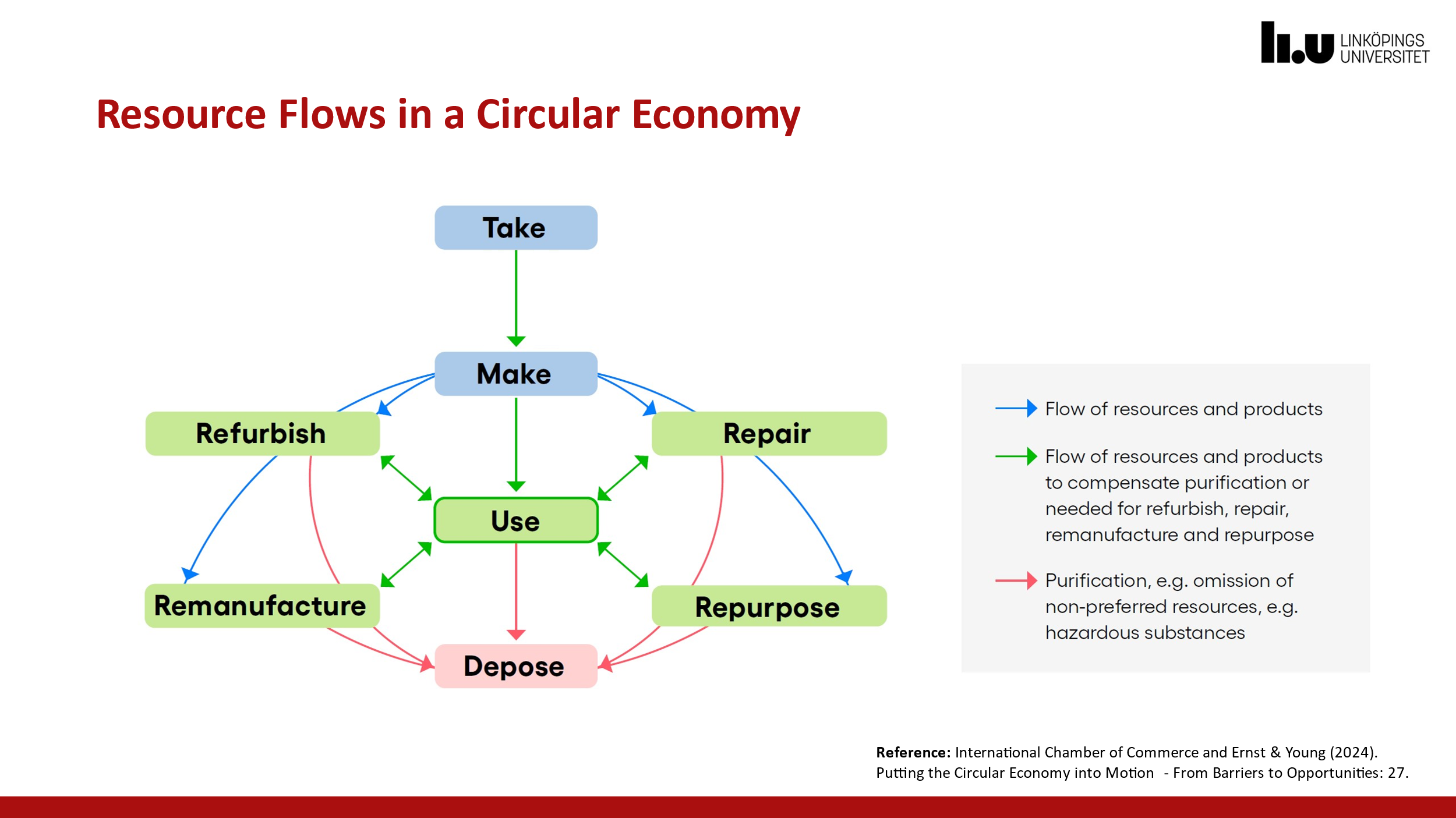

Lindahl presented an alternative model that would support a societal reframing of waste as a resource, which was part of a report from early October by the International Chamber of Commerce in Paris. He also identified the need for innovative business models that move away from the intense focus on sales that came to dominate much of the 20th century. In a circular economy, the focus should be on providing value over time rather than selling products.

The Mjölby-based company Toyota Material Handling took that direction in the early 2000s, analysing customer needs and reconceiving their business model. Lindahl described how they shifted from selling forklift trucks to instead offering a fleet of rentals.

– They have gone from rental contracts that were 3–5 years up to 10 or 12 years. When the customer doesn't need the forklift trucks any longer, they are taking the forklift trucks back and refurbishing them, fixing them into new ones, and putting them out for new customers, he said.

With a focus on rentals, they can deliver more and longer-term value to the customers. And the company gets additional value out of the spare parts and other forklift components, rather than tossing them out. What once may have been considered waste is now a resource.

Lindahals alternative model that would support a societal reframing of waste as a resource.

The surprising lesson in a hotel towel

Lindahl also believes that the new standard’s approach of defining waste as a resource will encourage people to value it more. Consumers still generally associate secondhand goods with lower quality and desirability, but that newer-is-better mindset can fall away with some strategic reframing.

He illustrated this with the example of used bath towels. People would probably not consider those to be equally valuable to brand new ones, but “fluffy white towels” at a hotel are a different story.

– I've been staying in a lot of hotels. I've never seen someone going down to the lobby complaining about the fact that they're using second-hand towels, he said.

Watch the full presentation from Future Day, along with a discussion with Professor Mattias Lindahl and Ragn-Sells' Chief Sustainability Officer, Pär Larshans: